Wall Street finally gets it!

This story was originally written by Alex Eule, Managing Editor of Barron’s and published here.

Subscription models are changing the relationship between businesses and their customers. And investors are mostly benefiting.

When Microsoft leapfrogged Apple last month to become the world’s most valuable company, the symbolism was rich, given the pair’s intertwined history. But the milestone carried a deeper significance about the future: Wall Street has recognized the value of subscriptions over traditional sales.

While Apple investors fret over the latest iPhone sales, the market has rewarded Microsoft for locking in a regular stream of revenue tied to the cloud and its Office 365 franchise. Those old Windows software boxes? They’ve been replaced by shiny mobile apps tied to monthly payments.

Sure enough, Microsoft (ticker: MSFT) shares rose 3.8% in November, even as Apple (AAPL) tumbled. Despite Apple’s user base of one-billion-plus iPhones, the company’s shareholders still worry every year about the next device. It’s an exhausting cycle for consumers, investors, and, surely, Apple itself.

Subscriptions offer a way off the product hamster wheel. Recurring payments have changed the way that Americans consume software, music, movies, television, fitness, clothing, and food. Even tractor maker Deere(DE) is trying to sell subscriptions to farmers. And the trend goes beyond Corporate America. Don Ward, who has shined shoes for 18 years just outside Barron’s offices in midtown Manhattan, began offering a subscription service in 2010. For $100 a year, customers get unlimited shines. For $500—the “platinum” service—customers get shoeshines for life.

“It helps me because I reward my most loyal customers,” Ward says. Plus, “who doesn’t want to get paid in advance?”

Consumers and businesses have found an unlikely alignment through subscriptions. Merchants can see revenue months down the road, while customers get convenience, customization, and the promise of ongoing service upgrades for one, all-you-can-eat price.

“The entire $80 trillion economy is up for grabs,” Tien Tzuo, CEO of subscription-billing platform Zuora (ZUO), writes in his new book, Subscribed. Zuora’s stock is up 30% since it went public in April. Its revenue is expected to grow 39% this fiscal year, to $234 million.

Investors, somewhat belatedly, have discovered the subscription payoff. The market now values Microsoft at $23 for every dollar of profit it generates, while Apple’s price/earnings ratio is mired at a hardware-like 13 times.

The valuation math illustrates how important subscriptions can be. Getting the model right can generate billions of dollars for shareholders. Take the rise of Netflix (NFLX), which trades at a sky-high 67 times projected earnings for next year. Wall Street has become more and more bullish with every passing quarter. And, as long as customers pay their monthly bill, no one is worried about the commercial success of its latest show.

While Netflix has taught the world how to build a subscription business from scratch, Adobe (ADBE) has demonstrated that old companies can remake themselves with subscriptions.

In 2013, Adobe stopped selling boxed versions of its Photoshop and other design software, which cost as much as $2,500. Instead, users are now pushed to pay from $10 to $50 a month for access to the products.

Customers complained loudly at first. They didn’t like the idea of a never-ending rental charge for Photoshop, when previously they could pay a one-time fee.

But the lower upfront cost attracted new customers, and Adobe earned customer satisfaction by layering new value into the subscription at the same price. Adobe’s Creative Cloud now includes photo storage in the cloud and mobile apps that sync across multiple devices.

In 2012—the last full year it sold boxed software—Adobe earned $2.35 a share. This year, the company is projected to earn $6.82, going to $7.98 next year.

It’s a stunning jump for a 36-year-old outfit. The stock’s gain has outpaced earnings growth because investors are paying more for every dollar of profit. The stock has risen 793% since Adobe outlined its subscription strategy in 2011. Adobe trades at 31 times next year’s earnings projections. In 2012, the multiple was 12.

“On earnings that are three times larger, the multiple has tripled,” says Barry Gill, head of active equities at UBS. “All of a sudden, the universe of buyers and the frequency of repurchases have expanded. Because of that, investors are prepared to pay a higher multiple.”

Some 90% of Adobe’s revenue is now classified as recurring, up from 5% before the transition, Adobe CEO Shantanu Narayen says.

Investors have also learned new ways to evaluate Adobe’s stock, freeing the company from earnings metrics that don’t generally align with customer happiness.

“Retention is the new growth,” Narayen tells Barron’s. The subscription model, he adds, has made the company more responsive, with developers tracking customer habits and updating software in nearly real time.

“What is so obvious in retrospect with a transaction-based software model is that you’re at least two steps removed from the end customer,” Narayen adds.

Not every company can be an Adobe or a Netflix, of course. The subscription model itself can’t generate demand or lower the cost of doing business. And as subscriptions proliferate, investors need to dig deeper into the dynamics of their models, says Aswath Damodaran, a finance professor and valuation specialist at New York University’s Stern School of Business.

“Many venture capitalists and public investors are pricing user-based companies on user count, with only a few seriously trying to distinguish between good, indifferent, and bad user-based models,” Damodaran wrote earlier this year.

It took the software industry a few years to find the best way to communicate its subscription strategy. But the power of the model is now clear. So-called software as a service, or SaaS, dominates business models. In addition to Microsoft and Adobe, Autodesk (ADSK) and Intuit (INTU) are among the software producers that are remaking their businesses as a subscription model.

“You’re now looked at strangely as a software company if you’re not using a subscription business model,” says Sterling Auty, software analyst at J.P. Morgan.

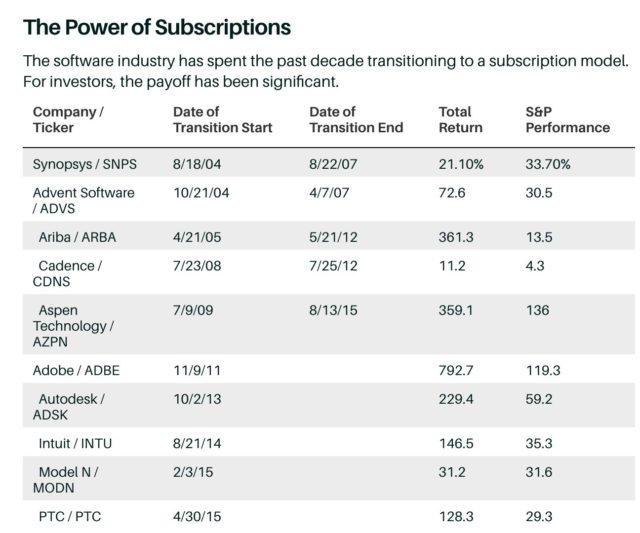

The transitions have produced stellar results for investors. Auty has tracked 12 subscription transitions since 2004, some of which are ongoing. During the transitions, the stocks have an average gain of 188%, versus 45% for the S&P 500.

Start-ups are taking subscriptions well beyond the software and tech world. Alan Patricof, a longtime venture capitalist, an early investor in Apple, and the co-founder and managing partner of Greycroft, says subscriptions are the clearest way around a difficult advertising world.

“We’re living in an environment where Facebook, Google, and Amazon are sucking up so much of the advertising revenue,” he says. “Subscriptions and e-commerce are an antidote to that.”

Greycroft has more than 200 companies in its portfolio. Its past investments include subscription services Plated and Trunk Club.

These days, Patricof sounds particularly excited about Osmosis, a medical- education company founded by former students of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. The company is selling subscriptions to popular videos that guide students through anatomy and other core medical school classes. Osmosis is now adding content for residency programs and continuing education.

“Fifty percent of what you knew in med school is out of date within five years of graduation. Literally, it’s lifelong learning,” Osmosis CEO and co-founder Shiv Gaglani says.

Osmosis’ goal is to retain medical professionals as customers from school all the way to retirement, with a payment every month or year along the way.

Gaglani says his average subscriber tenure has doubled from one year to two in the past 12 months “because we’re adding more content that keeps people engaged longer.” He cites streaming pioneer Netflix as the model: “Original content driving subscriptions.”

Netflix has paved the way for start-ups that recognize the value in growing up with paying customers by their side basically from the start.

“Customers are giving us a 0% interest loan, and then we’re using that loan to build out content for them,” Gaglani says. Osmosis recently raised $2.5 million from Patricof’s Greycroft and others.

Peloton, the private spin-bike company, is further along in its subscription evolution. The company sells its at-home bike for $2,000. Users then pay $39 a month to access classes streamed over a tablet attached to the bike.

Peloton has long argued that the subscription is a bargain, compared with charges at spin studios like SoulCycle, where each in-studio class can be $30 or more. Peloton says its at- home bike is ridden an average of 10 times a month.

Over time, Peloton has added additional content, including running and stretching. It’s starting a yoga program at the end of December. The subscription price has remained constant.

“Never say never, but I see it as our golden goose, and that $39 price point is sacrosanct to me,” Peloton CEO and co-founder John Foley tells Barron’s. “You have to do delightful things and leave money on the table.”

Foley says subscriptions are the key to Peloton’s version of at-home fitness. “The monthly service is what you really buy,” he says. “That was the flaw with the old models. It was just hardware.”

Some of Peloton’s subscribers use their own equipment and stream classes over mobile devices. They pay $19 a month. The six-year-old company’s monthly churn—customer defections—is “dramatically less than 1%,” Foley says. (Netflix doesn’t disclose its churn, but Morgan Stanley estimates it at 2% to 3% monthly.)

Earlier this year, Peloton raised $550 million, which values the New York– based start-up at about $4 billion. An initial public offering is the likely next step.

Foley wouldn’t comment on current timing, but the company has previously talked about a 2019 public debut. One question is how public markets will react to the business model and Peloton’s unique mix of subscription data.

“We’re anxious about the Street understanding how beautiful our business model is, because there’s nothing else like it,” Foley says.

A Peloton spokeswoman says its U.S. bike business is currently profitable, but the company is planning to invest further in product, retail, and international opportunities. “As a result, like most well-capitalized, fast-growth companies, we don’t expect to show profitability for some time.”

Initial public offerings have tripped up some subscription plays. Blue Apron (APRN), the subscription meal service, has fallen almost 90% since its June 2017 IPO. Blue Apron ultimately spent too much money attracting new customers. Cost of acquisition is subscription kryptonite.

Damodaran, the NYU professor, says, “We’re letting [companies] get the upside of these numbers. But we’re not asking them the questions we need to ask to see if the numbers pay off.”

He has calculated the economics of two subscription models: Netflix and Spotify Technology (SPOT). The major difference, he writes, is how the companies pay for content. Netflix pays once and gets economies of scale with every additional subscriber, whereas Spotify’s cost basis is pegged to the number of song listens.

“As a result, Netflix derives much higher value from both existing and new subscribers,” he wrote in May.

After adjusting for costs, Damodaran estimates that an existing Netflix subscriber is worth $509, with new subscribers worth

$398. For Spotify, he gets a value of $109 for existing subs and just $81 for each additional user.

Damodaran tells Barron’s that it’s also important to understand the distribution of usage across a customer base. He says that Uber and Lyft, for instance, can’t afford to offer subscriptions because a small percentage of users make up a majority of revenue. If those customers get an all-you-can-eat plan, revenue dries up. “That’s what MoviePass missed,” he says. In 2017, the much-heralded subscription service began offering a one-a-day movie plan for just $10 per month.

“They were offering subscriptions to moviegoers on the false premise that they were charging more for subscriptions than the average moviegoer paid. But it was the avid moviegoer who bought the subscription.”

The stock of MoviePass’ parent company was $8,225 a share in October 2017, on a split-adjusted basis. Today, it trades for two cents.

Now, AMC Entertainment (AMC), the country’s largest theater chain, is dealing with the aftermath. AMC introduced its own subscription program called Stubs A-List. The $20-a-month program allows subscribers to see three movies a week, including more expensive IMAX and 3-D shows.

During its November earnings call, AMC said that A-List was exceeding expectations, with 500,000 sign-ups in the first five months. That apparently sparked concerns of a MoviePass 2.0. AMC shares tumbled 14%, despite generally good news on the earnings front.

“The failure of MoviePass is making it more difficult for AMC to get its subscription model past investors—even though AMC is a much better business model,” Damodaran says. “It has made investors much more conscious.”

AMC CEO Adam Aron says the company has done its homework and struck a balance between ticket sales and subscriptions. A-List subscribers are averaging 2.7 visits a month, he says, in line with company estimates. “The vast majority of people coming to AMC will come the old-fashioned way: one ticket at a time,” he says. But in just a few months, roughly 10% of attendees are already coming from the subscription program.

“Who knows where this will settle out,” Aron says. “But you could make a pretty strong case that, if it were to top out at 20%, then we ought to be getting a subscription multiple, rather than a traditional movie theater multiple. And the reason that subscription multiples are higher is this notion that you don’t need to find the customers over and over again. You’ve already found them.”

Based on enterprise value, AMC trades at seven times next year’s Ebitda, or earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. Netflix’s comparable multiple is 44. Even if AMC’s multiple goes to 10, its stock is worth $41, or nearly three times its current value.

Subscriptions, meanwhile, are resonating with younger viewers. The company says 27% of A-List subscribers are 30 or under.

In the latest quarter, A-List helped grow attendance at AMC, Aron says, a rare feat in an industry that has seen annual attendance declines for the past 20 years.

“I think you’re going to continue to see with the success of A-List, more people going to the movies more often. That is good for Hollywood, and that’s good for us as a theater operator,” Aron adds. “And it’s great for consumers.”